Issue 19: Case by case: News coverage of child sexual abuse

Sunday, May 01, 2011No one likes to talk about child sexual abuse. Yet tens of thousands of children are sexually assaulted every year in the United States.1 A matter this serious and pervasive deserves attention.

News coverage in particular is important because it puts issues in front of the public and in front of policy makers. News coverage of child sexual abuse is doubly important because the abuse is often hidden from view. For many people — including many policy makers — news coverage will be the only way they learn about the issue.

Occasionally, a headline-grabbing story puts child sexual abuse on the public agenda. One recent example occurred in 2002 and 2003, when revelations about abuse in the Catholic Church surfaced.2 After the story broke, ongoing coverage forced the church to respond. Among other concessions, U.S. Catholic bishops adopted a revised policy on child sexual abuse in 2002.3 Media exposure also resulted in legal pressure to compensate victims: As of 2009, the Catholic Church has paid more than $2.6 billion in such abuse-related costs.4

Prominent events like the revelations about abuse within the Catholic Church can propel the issue into the spotlight. But how do journalists cover child sexual abuse in the absence of a prominent case? Do they cover it routinely? Do sensationalist stories focusing on the “stranger danger” misconception (that victims of child sexual abuse do not know their abuser) dominate news coverage? Or does the news reflect the prevailing patterns of child sexual abuse? Is preventing child sexual abuse discussed? In this framing memo we examine how child sexual abuse is portrayed in the news.

What we did

To understand how child sexual abuse is covered, we selected a representative sample of U.S. news, then coded the content in detail.

Selecting the sample

We sampled newspapers because their content is available in easily accessible archives, allowing us to examine several years of news coverage, and because newspapers typically set the agenda for other media, including television news and blogs.5 Using an extensive set of keywords, we searched the Nexis-Lexis database for child sexual abuse articles that appeared in U.S. newspapers from 2007 through 2009.

We examined coverage from 2007-2009 so that we would have a substantial recent time period yet avoid the bulk of news coverage related to the Catholic Church abuses reported during 2002-2006. While those revelations — and the pressure on the church to prosecute offenders — were extremely important, we didn’t want the coverage of one institution to overwhelm what we might see in general coverage of the issue. Our final sample included only news and opinion articles that dealt primarily with child sexual abuse.

We also wanted to be sure the sample was representative of all national newspaper coverage. We selected a chronological random sample so there would be equal numbers of each day of the week (the same number of Mondays, Tuesdays, etc.) for each year of study.6 This helps guard against distortions that could come from a sample loaded with fat Sunday papers that might be heavy on feature stories, or thin Monday papers light on news. The random sample also guards against a major news event dominating coverage. This was important because we wanted to see how child sexual abuse is routinely covered. We constructed two weeks for each year for a total of 42 days of news coverage.

Coding the sample

We developed a coding protocol to document patterns and themes in the coverage. We began by adapting coding protocols from our previous studies on violence, as well as measures used by other published work on child sexual abuse in the news.7 8 9 10We used an iterative process until we reached satisfactory inter-rater reliability (Krippendorf’s alpha >0.7) for all coding measures.

What we found

Newspaper coverage

Our search yielded 348 articles on child sexual abuse reported on our sample days in U.S. newspapers from 2007 through 2009. After we eliminated duplicates and articles that mentioned child sexual abuse only in passing, we had 260 substantive articles on child sexual abuse to analyze. Most of the articles (93%) were news or feature stories. The remaining items were editorials, op-eds, letters to the editor, and columns.

The overwhelming majority of articles (236, or 91%) focused on one or more specific child sexual abuse incidents. The remaining 24 pieces reported on a general theme relating to child sexual abuse (such as the stranger danger misconception), but did not include details of a specific incident.

What were the stories about?

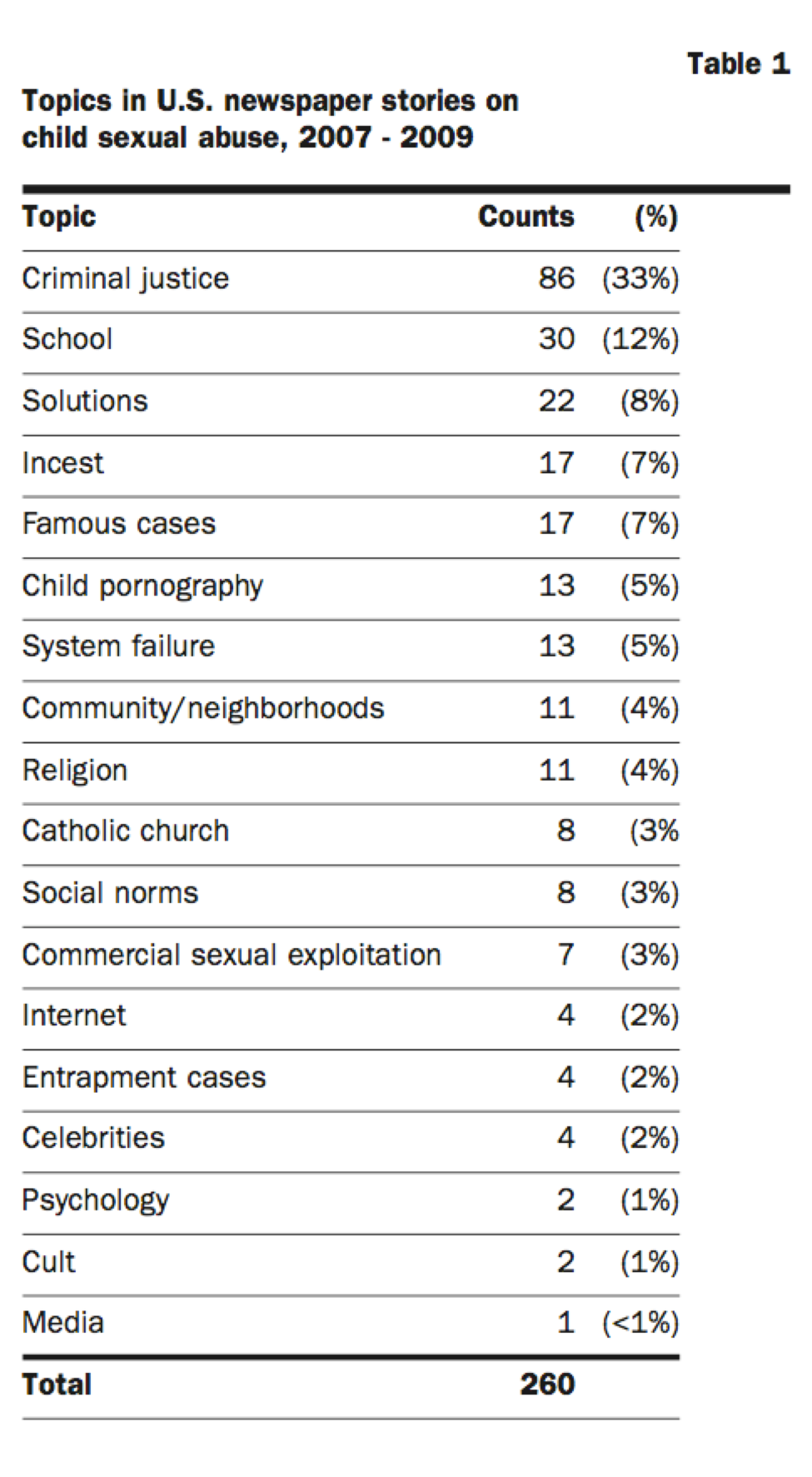

The most common topic (33%) of child sexual abuse coverage was criminal justice, such as arrests and trials of accused perpetrators (see Table 1). Another 12% focused on abuse that occurred in a school setting or described the accused as a teacher or school official. Solutions — including both policy solutions, such as legislative directives to track child pornography on the Internet, and community programs like counseling for victims of sexual assault or prevention education — were the focus of 8% of the coverage. Stories about incest comprised 7% of the coverage. Famous cases of child sexual abuse, such as international cases that attracted domestic coverage (including a bust of one of the largest Internet child abuse rings in Britain) were the subject of 7% of the stories. Stories about the manufacture, distribution, and apprehension of child pornography were the focus of 5% of the coverage, as were pieces about the failure of social systems such as foster care.

The remaining topics included stories about community members’ reactions to child sexual abuse (4%); child sexual abuse committed by non-Catholic religious officials (4%); child sexual abuse within the Catholic church (3%); social norms or beliefs (such as “stranger danger”) that contribute to misperceptions about child sexual abuse (3%); the commercial sexual exploitation of children, including international cases (3%); the role of the Internet in both promoting child sexual abuse and apprehending predators (2%); instances where law enforcement entrapped a potential offender (2%); cases of child sexual abuse involving celebrities such as R. Kelly (2%); the psychology of perpetrators and victims (1%); cases of child sexual abuse that occurred in religious sects, such as evangelist Tony Alamo’s compound (1%); and, in a few self-reflexive stories, media coverage of child sexual abuse (<1%).

Why were the stories in the newspaper?

Child sexual abuse happens every day, but few incidents are covered. We wanted to know: When child sexual abuse is covered in the news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Many factors can influence the news selection process, from the details of the incident itself to what else competes for coverage that day. Reporters commonly refer to the trigger for a story as a “news hook,” so we identified the news hook for each article that addressed the question “Why was this article published today?”

Child sexual abuse was most often covered when there was a criminal justice event related to the aftermath, such as an arrest or a trial (73%) (See Table 2 below). Controversies, such as disputed verdicts in child sexual abuse cases, were the news hook in 7% of pieces. Breakthroughs (such as new findings in older cases) and milestones (including the anniversaries of past events) were the next most prominent news hook, each found in 6% of the articles. Other news hooks included: stories about local events, such as community meetings or reports (4%); false imprisonment and other injustices (2%); stories in which the victim or accused was particularly unusual such as a story about a man who escaped jail by virtue of his short stature (2%); and stories that focused on pop culture events like the release of the movie Precious (1%).

How was the act characterized?

Estimates indicate that in 90-95% of cases of child sexual abuse, the victim knows his or her abuser.11To see if news coverage accurately reflected this pattern, we classified the relationship between the victim and the accused as described in each article. We also noted how the sexual assault was described.

- Relationship between the victim and accused: In the overwhelming majority (70%) of news on child sexual abuse from 2007-2009 in which a specific case of abuse was described, the victim knew the accused. Of these articles, 29% described a situation in which the accused was an authority figure, such as a coach, teacher, or religious official. In 23% of articles, the accused was an acquaintance of the victim or of the victim’s family. The accused was a family member in 18% of these stories.12 The accused was described as a stranger in only 4% of the news. In 26% of stories, the relationship between the child and the abuser was not specified at all.

- Abuse type: The finding that many articles did not describe the relationship between the victim and the accused was just one example of the ambiguous language we found in news coverage of child sexual abuse. The language used to describe the incidents was also broad, inconsistent, and suggestive rather than precise. For example, one story described the arrest of a man accused of “molesting” a child. The child told police about the “alleged abuse” and described being “sexually assaultedon several occasions.”13 Even when the article included information about a specific criminal charge, the language used to describe these crimes was often ambiguous. In one article, a California man was charged with “lewd and lascivious acts with a child” and “continuous sexual abuse of a child.”14 We saw these terms, along with phrases like “sexual acts” and “inappropriate sexual behavior,” in many articles. Legally, these phrases can encompass a variety of different acts, and the definitions may vary by jurisdiction.

What did the news say we should do about child sexual abuse?

A crucial step toward ending child sexual abuse is putting prevention on the public agenda.15 16 To determine if news coverage addressed responses to child sexual abuse, we first identified all references to prevention or interventions in the coverage. Then we organized solutions by their intended target: individuals or the broader environment (see Table 3). We identified a solution as operating at the individual level if it focused only on the children or perpetrators involved in a case; environmental level solutions incorporated a role for families or organizations, or broad efforts to change the media, government responses, or other institutions.

- Solutions

Less than one-third of the news (78 articles) mentioned solutions for child sexual abuse (Table 3). The majority of solutions were interventions designed to address child sexual abuse that had already happened (82%), rather than preventive measures to reduce future child sexual abuse (18%). The most frequently proposed interventions called for stronger criminal justice responses at the societal level, such as building more prisons to house offenders or calls to improve a city’s criminal justice response to child sexual abuse. We also saw criminal justice interventions aimed at individuals (e.g. longer terms for a particular offender).The solution mentioned most often was prevention education. Prevention education was presented as a small-scale, highly individual solution. For example, a typical article reported on a program that “reinforces parenting as the primary way to prevent child sexual abuse.”17 Few articles discussed establishing education programs through larger institutions (such as schools or hospitals), or other broader scale prevention activities: One example was a story that advocated counseling to teach individuals who are attracted to children (but have not yet abused) how to control their behavior before they act. This is a particularly rare example of a solution that addresses the behavior of perpetrators. More commonly, stories about prevention education focused on the behavior of children and their parents. - Barriers and misperceptions

Advocates argue that the social stigma associated with child sexual abuse deters victims from coming forward and prevents society from addressing the issue. Therefore, advocates want to see news coverage include stories about the social stigma of being a victim of sexual abuse, victims’ reluctance to come forward about the assault, and the lack of resources for prevention and treatment programs. But very few articles (13%) mentioned such barriers to preventing child sexual abuse. Only 6 articles (2%) expressly addressed possible misconceptions about child sexual abuse, such as the tendency to focus on extreme cases like the misdirected concern for “stranger danger.”

Who speaks in stories about child sexual abuse?

As we would expect given the topics of the stories, the speakers quoted in the news were most often criminal justice professionals, including state justice department representatives (38%). In most cases, criminal justice professionals commented on the status of individual cases, rather than on larger issues affecting child sexual abuse. However, in some cases, these professionals spoke more generally about the role of the criminal justice system in prosecuting child sexual abuse. For example, one detective commented on the challenge of getting a confession from a potential perpetrator, saying, “If you can’t get the perpetrator to talk, the child suffers.”18

Victims and their families were the second most frequently quoted source (17%). Most victims or family members provided emotionally charged details about their experience, as when a victim wept, “I don’t want to remember,” while describing her experience.19 In rare instances, victims advocated for solutions to child sexual abuse, as with the adult survivor who argued, “we have to start to say as a society we will not allow this to happen, not [give perpetrators] 18 months and a slap on the wrist.”20

Advocates representing child sexual abuse advocacy organizations were the third most frequently quoted speakers (12%). A few of these speakers discussed solutions, such as “resources that moms can turn to when they need help to get out of situations that are potentially harmful to their kids.”21 However, most child sexual abuse advocates did not discuss solutions, but instead spoke passionately about the horrors of victimization, as did the nonprofit leader who described a family that “lost their child to the most hideous and heinous crime.”22

How were the stories framed?

The structure of news stories can also influence a news consumer’s interpretations. Communications researchers have found that news stories are generally structured as either episodic — that is, framed around a singular person or event — or thematic — focused on the broader context surrounding the news event.23 24 Other research has found that the majority of child sexual abuse coverage is episodic,25 focused on an isolated incident of child sexual abuse. Strictly episodic frames do not inspire readers to consider the issue in a broader social context.26

Our findings are consistent with this research. We found that most of the coverage of child sexual abuse was episodic (80%), highlighting a specific crime. The rest of the news on child sexual abuse (20%) was thematic, including statistics or other contextualizing information. One thematic article, for instance, reported, “most victims know their abuser, with about one in three assaulted by a resident.”27Most of the time, however, when news consumers read about child sexual abuse, it is in terms of isolated incidents disconnected from larger patterns or circumstances.

Conclusions

Clear patterns emerged in three years of news coverage of child sexual abuse. First, child sexual abuse remains largely out of view. While child sexual abuse appears regularly in news coverage, there is, on average, less than one story a week on the topic and even fewer that cover the issue in depth.

Second, when child sexual abuse is covered, it is usually because an incident of child sexual abuse has achieved some milestone within the court system (e.g., trial of the accused). As a result, when people are exposed to child sexual abuse in the news, it is likely associated with isolated episodes viewed through a criminal justice lens.

Third, prevention remains virtually invisible. Solutions were discussed in less than one-third (30%) of the coverage. Most of those stories were about interventions focused on treatment after the fact. Few discussed prevention.

Fourth, the language that describes child sexual abuse in news coverage is often vague. The terms were inconsistent and often suggestive rather than precise. Many news articles did not specify the type of sexual abuse, and those that did often buried the specifics far down within the article. The descriptions are complicated by the fact that legal definitions may vary from place to place.

One bright spot in the analysis is that the idea that strangers or “predators” perpetuate child sexual abuse was infrequent; more often than not, we found child sexual abuse attributed to someone with whom the child is familiar.

Implications of reporting child sexual abuse through a criminal justice lens

Criminal justice responses to child sexual abuse (such as longer prison terms) dominate coverage of the issue. This approach appears forcefully, as in one story in which a judge, explaining a particularly long sentence for an accused pedophile, says the sentence was meant to “send an unequivocal messagethat anyone who sexually abuses children will face significant penalties.”28Such sentences are likely appropriate, and deserve news coverage, and, in fact, would not have the deterrent effect the judge desires without news coverage. However, if child sexual abuse is seen only as a series of crimes for which criminal justice is the most appropriate response, prevention will not be visible. The criminal justice lens limits the depictions of child sexual abuse because it tells stories exclusively from the perspective of the police, courts, and jails. It means the coverage focuses on instances of abuse that have already happened, making it more difficult for news stories to include discussion of what we might do about child sexual abuse before it occurs.

Some coverage included critiques of the criminal justice system, as when advocates voiced concerns about the impartiality of judges, the reliability of testimony from child witnesses who are victims of child sexual abuse, and the equitable enforcement of child sexual abuse legislation, as in the case of a 17-year-old boy tried as a child molester for consensual sex with a classmate. These are all important perspectives that warrant news coverage, but they don’t substitute for broader coverage of how to prevent child sexual abuse.

The form criminal justice stories take also works against reporting the broader context of child sexual abuse. Because the stories are usually limited to the next step in a process through the courts, they are reported episodically, as quick snapshots of what is happening at this point in time, rather than with a broader perspective on the issue of child sexual abuse. Research has shown that episodic stories make it easier for news consumers to blame the victim, while thematic stories that include some context make it easier for readers to understand shared responsibility for problems across government and institutions.22 Episodic criminal justice stories, then, could be reinforcing ideas that the problem is too big or complicated to address. More frequent thematic stories would help policy makers and the public envision solutions and prevention.

Overall, with the bulk of coverage focused on isolated events making their way through the criminal justice system, news coverage is not making it easier to see, understand, or talk about the broader issue of child sexual abuse.

Recommendations for advocates

Don Hewitt, legendary producer one of the most successful news programs ever, once said, “60 Minutes does not cover issues; it tells stories.” The same is true for every news organization. To expand news coverage about child sexual abuse, advocates will have to create news about the topic so reporters have different sorts of stories to tell. Stories require characters, scenes, and plots. The challenge for advocates is to imagine stories in which the character is not a sexually abused child. Instead, the characters in news stories could be those who are trying to prevent child sexual abuse; the scene could be schools, neighborhoods or other sites where environments need to change so prevention can flourish; and the plot can be what is happening to encourage — or thwart — broad-scale prevention efforts. Recent news coverage on child sexual abuse suggests several opportunities for advocates to expand the story on child sexual abuse, including:

- Create news about child sexual abuse.

Child sexual abuse has intermittently attracted extensive media attention (as in 2002-2003, when reporters covered the scandals in the Catholic Church). Advocates can build on these groundswells of media attention to change policies and public opinion around this issue, but they must be prepared to “piggyback” on breaking news about child sexual abuse. That is, they must be ready to respond immediately to current and notable stories (as in 2011 when an 11-year-old girl was gang raped by 18 boys and men in Texas 29) with strong, timely news stories and messages that are linked to prevention.Even when attention-grabbing stories about child sexual abuse are not in the news, advocates can work to expand the range of stories on child sexual abuse so it is not represented solely as a criminal justice issue. To do that, they need to create news about other aspects of child sexual abuse. Introducing legislation or other policy initiatives can provide a good news hook, although that is likely to be infrequent. Advocates can also release studies, create community events, give awards, or find other newsworthy ways to bring attention to the issue — and what should be done to prevent it — outside of what happens in a specific case after the abuse is reported. - Advocate for systemic solutions.

Solutions-focused stories increase desire and support for collective action around children’s issues and inspire actions on children’s behalf.30 But reporters can only write about solutions to child sexual abuse if advocates take action and talk about solutions. In recent news coverage, we found few discussions of solutions beyond some references to criminal justice responses that are “stranger oriented” (such as proposals for following registered offenders after their release from prison). - Advocates should articulate the policy and environmental changes that can prevent child sexual abuse, succinctly present those solutions in simple terms, and be prepared to talk with reporters about who can implement them. If this is the story advocates want to see, they need to create news that makes it easier for reporters to tell this story.

- Contribute to the op-ed pages, write letters, and suggest editorials.

We found very little opinion in newspapers about child sexual abuse. However, in the past, child sexual abuse coverage was more or less evenly divided between news and opinion pieces.31 There is a precedent for opinion writing on this controversial issue, and advocates can make regular use of opinion space both in newspapers and in new media, such as blogs and social media venues. Advocates should monitor the news so they can respond with timely opinion pieces and letters to the editor. They should meet with editorial boards and request editorials supporting prevention. All of these tactics will be more effective if they are linked to advocates’ overall strategy for preventing child sexual abuse. - Talk about the context surrounding child sexual abuse.

To create an environment that promotes prevention and is supportive of child sexual abuse victims and families, advocates’ messages must go beyond the simple criminal justice details presented in news coverage to illustrate the landscape that surrounds child sexual abuse. Advocates should be practiced at describing the context in which child sexual abuse occurs and the specifics regarding the policies and programs that need to be established, supported, and maintained to prevent child sexual abuse. - Be sure spokespeople, especially survivors, are well prepared to articulate solutions and prevention.

Adult survivors of child sexual abuse can be powerful authentic voices for victims and for policies that will institute prevention. Because of their age and maturity, they may be better able to put their experiences in a larger context than would younger victims with similar histories. Advocates should work with motivated adult survivors to develop their advocacy skills, including readiness to talk about policy change with reporters, so those who want to are confident and prepared when they speak publicly.

Recommendations for reporters

It will be hard for policy makers and the public to fully understand child sexual abuse — and what can be done to prevent it — if journalists continue to restrict their reporting to the events surrounding the arrest and trial of perpetrators. Those stories are important, but the public needs more. While this study demonstrates that most news coverage of child sexual abuse focuses on such isolated events, the same coverage also demonstrates that reporters can find newsworthy angles and emerging stories that go broader. Reporters can expand their stories by introducing the context of child sexual abuse, the consequences for victims, perpetrators, their families and communities, and provide resources for personal safety as well as civic action. To do that, reporters can:

- Push authorities for solutions.

News coverage of child sexual abuse most often appears connected to actions by law enforcement or moments in the criminal justice process. But if the coverage stops there, the public will learn little about prevention. Reporters should ask: What are local communities doing to prevent child sexual abuse? Is it working? Could it be done in this community? What do advocates or government officials think should be done? Is it reasonable? If so, why hasn’t it happened here? - Be precise in descriptions of child sexual abuse.

Reporters should work with advocates, medical practitioners, law enforcement, and the courts to find appropriate but precise language for describing child sexual abuse. Finding the right language to describe incidents of child sexual abuse is challenging; the news needs to be specific so the public understands the depth and nature of the problem, but news coverage also must avoid being prurient or sensationalistic. New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd recently demonstrated that it is possible to write explicitly about child sexual abuse, and that such language helps readers understand the magnitude of the problem. Dowd’s 2011 column about the abuse in the Catholic Church included non-euphemistic descriptions of the rape of two alter boys.32 The article generated letters and comments from readers who “for the first time read what actually took place between these men and young boys.”33 Even after years of exposure to vaguely worded stories about the scandal, the more precise language startled and appalled readers, who were motivated to think about the issue and respond to the article.Precise descriptions of sexual abuse may have the benefit of humanizing victims. Other research on intimate partner violence has found that details about perpetrators, but not victims, are often included in stories. The consequence is that the accused is humanized, while the victim is not.34 Reporters should consider other ways to bring a human face to victims of child sexual abuse, including precise descriptions of the abuse, and still maintain their privacy. This will be important, though difficult. - Look beyond criminal justice.

The news routinely covers the consequences faced by those accused of child sexual abuse in terms of criminal justice. However, consequences for victims and families were seldom reported outside that context. Ignoring the effects of child sexual abuse on children and families leaves out an important part of the story that can help the public understand recovery and social consequences. Reporters should follow up stories about incidents of child sexual abuse with stories that examine the consequences for victims, perpetrators, and their families in the context of their lives and communities. What happens to a family when child sexual abuse happens? What happens a year later? What happens to schools, religious congregations, or other community institutions? What do these consequences help us understand about child sexual abuse, and what to do about it? - Identify the relationship of perpetrators to the child.

Language that describes the relationship of the accused and their victims should be as unambiguous as possible, even though reports on specific crimes can’t always include details. Help readers avoid the myth of “stranger danger” (sometimes expressed using phrases like “child predator”) by investigating and clearly identifying the relationship of the accused to the victims. Data show that the overwhelming majority of children who are sexually abused are molested by someone they know, such as a parent, guardian, coach or teacher. Though journalists often described the familiar or familial relationship between perpetrators and their victims, more than one quarter (26%) of stories did not identify the relationship between perpetrators and their victims. If this relationship is not specified, readers may fall back on the “stranger danger” or “predator” misconception, which is particularly damaging because it does not inspire readers to think about the causal roots of child sexual abuse.35The conundrum for reporters is that because, in fact, “stranger danger” is unusual, that alone may qualify an incident as newsworthy. However, if news coverage overemphasizes the unusual by reporting it repeatedly, policy makers and the public will not understand the true nature of child sexual abuse, and so will be less likely to fashion appropriate and meaningful solutions. In this instance, story selection is as important as how the story is framed. - Pursue stories that examine the social, cultural, political, and economic aspects of child sexual abuse.

Investigate cultural trends and depictions of child sexual abuse, including self-examinations of media portrayals. For example, have television programs like To Catch a Predator turned child sexual abuse into a spectator sport? What do pediatricians and media scholars think? What businesses profit from child pornography and are they being challenged? What is the role of health care professionals or educators in preventing child sexual abuse? If reports of child sexual abuse have declined in a particular region, why? What do health professionals, legal scholars, survivors, and advocates think?

Issue 19 was written by Lori Dorfman, DrPH, Pamela Mejia, MPH, Andrew Cheyne, CPhil, and Priscilla Gonzalez, MPH. Pamela Mejia and Priscilla Gonzalez coded the articles. Thanks to Katie Woodruff, MPH, Cordelia Anderson, MA, and David Lee, MPH, for their thoughtful contributions to this research.

This research was commissioned by the Ms. Foundation for Women. We thank Ellen Braune, Patricia Eng, Irene Schneeweis, Brenna Lynch, and Monique Hoeflinger for their support and collaborative involvement in the study design.

References

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009. Child Maltreatment 2009. Available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/index.htm#can. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

2 Cox, C. 2003. Abuse in the Catholic Church. Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. Available at http://dartcenter.org/content/abuse-in-catholic-church. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

3 Public BroadCasting Service. 2002. US Bishops Adopt New Sexual Abuse Policy. PBS Newshour. Available at http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/catholic_06-14-02.html. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

4 Zoll, R. 2009. Catholic bishops warned in ’50s of abusive priests. USA Today. Available at http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2009-03-31-catholicabuse_ N.htm. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

5 Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism. 2009. New Media, Old Media: the Blogosphere. Available at http://www.journalism.org/analysis_report/blogosphere. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

6 Riffe, Daniel, Aust, Charles F., and Lacy, Stephen. 1993. The Effectiveness of Random, Consecutive Day and Constructed Week Samples in Newspaper Content Analysis, Journalism Quarterly 70: 33-139.

7 Cheit, R.E., Shavit, Y., Reiss-Davis, Z. (2010). Magazine Coverage of Child Sexual Abuse, 1992-2004. Journal of Child Abuse, 19(1): 99-117.

8 Thorson, E., Dorfman, L., and Stevens, J. Reporting Crime and Violence from a Public Health Perspective. Journal of Institute of Justice and International Studies, (2):53-66, 2003.

9 McManus, J., Dorfman, L. Distracted by Drama: How California Newspapers Portray Intimate Partner Violence, Issue 13: Berkeley Media Studies Group, January 2003.

10 McManus, J., Dorfman, L. Youth Violence Stories Focus on Events, Not Causes. Newspaper Research Journal, 23(4):6-12, Fall 2002.

11 Snyder, Howard N., and Sickmund, Melissa. 1999. Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 National Report. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

12 For purposes of this study, in situations in which the accused had “married” the underage victim, as in stories relating to evangelist Tony Alamo, the accused was coded as a family member.

13 City News Service. Police have arrested a Los Angeles Unified School District Employee today. City News Service, April 4, 2009.

14 Tribune staff. Covina man faces San Bernardino County child molestation charges. San Gabriel Valley Tribune. March 16, 2007: Breaking News.

15 Darkness to Light. Prevention Programs: Community Initiatives. Available at http://www.d2l.org/site/c.4dICIJOkGcISE/b.6143349/k.6366/Community_Initiatives.htm. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

16 Stop It Now! Together We Can Prevent the Sexual Abuse of Children. Available at http://www.stopitnow.org/node/2191. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

17 Brackenbury, Mark. Group offers tips on preventing child sex abuse. New Haven Register. May 2, 2008:B3.

18 Clark, A. On the trail of child predators. Lexington Herald Ledger. June 21, 2009: 1DA.

19 Taylor, V. Chambersburg man on trial for sexual abuse of children expected to testify today. Chambersburg Public Opinion. May 13, 2008.

20 Meyers, J. Rallying the community to shine light on child abuse. The Spokesman Review. July 17, 2007: B2.

21 Bennett Williams, A. A mother’s duty: When it’s shirked, tragic tales unfold: Kids caught in the middle in failure to protect. The News-Press. October 28, 2007: A1.

22 Reed, L. Deadly sex assault on child: Parents “can’t stand” to live in home where girl, 3, was killed. Omaha World-Herald. May 27, 2009: A1.

23 Iyengar, Shanto. 1994. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

24 Major, L. (2009). Break it to Me Harshly: The Effects of Intersecting News Frames in Lung Cancer and Obesity Coverage. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives, 14(2), 174-188.

25 Kitzinger, J., Skidmore, P. 1995. Playing safe: Media coverage of child sexual abuse prevention strategies. Child Abuse Review, 4(1): 47-56.

26 Post, L.A., Smith, P.K., Meyer, E. Media frames of intimate partner homicide. In Stark E, Schlesinger Buzawa E, ed. Violence against women in families and relationships. New York: Praeger/Greenwood; 2009.

27 Editorial staff. Editor’s note. The Oregonian. May 2, 2008.

28 State News Service. Nottawasepii Huron Band of Pottawatomi Member Sentenced to 25 Years for Sexually Assaulting Minor on Pine Creek Reservation. State News Service, August 27, 2009.

29 Brisbane, A. Gang rape story lacked balance. The New York Times. March 11, 2011. Available at http://publiceditor.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/11/gang-rape-story-lacked-balance/. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

30 The TOPOS Partnership. (2010). Solutions storytelling: Messaging to mobilize support for children’s issues. Available at http://www.childadvocacy360.com/content/solutions-storytelling-messaging-mobilize-support-childrens-issues/. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

31 Kitzinger, J., Skidmore, P. (1995) Playing safe: Media coverage of child sexual abuse prevention strategies. Child Abuse Review, 4(1): 47-56.

32 Dowd, M. Avenging altar boy. The New York Times. March 15, 2011. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/16/opinion/16dowd.html. Retrieved March 23, 2011

33 Briglia, D. Letter: Church Sex Abuse. The New York Times. March 20, 2011. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/21/opinion/l21dowd.html?_r=1&ref=letters. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

34 Post, L.A., Smith, P.K., Meyer, E. Media frames of intimate partner homicide. In Stark E, Schlesinger Buzawa E, ed. Violence against women in families and relationships. New York: Praeger/Greenwood; 2009.

35 Collings, S. (2002). Unsolicitied interpretation of child sexual abuse media reports. Child Abuse and Neglect, 26(11): 1135-1147.