Trauma, resilience, and #blacklivesmatter: How do racism and trauma intersect in social media conversations?

Friday, June 01, 2018The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente launched a groundbreaking study in 1995 that provided conclusive evidence that traumatic incidents in childhood (like witnessing domestic violence or experiencing sexual abuse) are associated with a higher risk of many damaging physical and mental health consequences.1 These traumatic incidents are called “adverse childhood experiences,” or ACEs, and cause toxic stress. Toxic stress is the body’s physiological response to extreme, frequent, or prolonged adversity and can disrupt the development of vital organs and the nervous system.2 The more ACEs an individual has, the more toxic stress accumulates, and the greater his or her risk for a range of poor mental and physical health outcomes in adulthood, including diabetes, cancer, substance abuse, and suicide.1

One of the more important findings from the ACE study was that harmful childhood traumas are very common.3 And although trauma can affect everyone, some communities suffer disproportionately.

The original ACE study focused on traumatic experiences as a result of abuse or dysfunction within families. Subsequent ACE surveys have expanded the definition of childhood trauma to include trauma related to structural factors, such as exposure to racism, poverty, involvement with the foster care system, and living in an unsafe neighborhood4, 5 — all experiences that disproportionately affect people of color and low-income communities.

However, despite the greater burden of traumatic experiences carried by communities of color, communicating about childhood trauma and its connections with race and racism can be challenging.

Experts are divided as to whether to emphasize the universality of childhood trauma or to highlight the experiences and needs of communities of color that experience a higher burden of violence and trauma.5

We wanted to better understand how racism and childhood trauma are being discussed, together and separately. One place where conversations about both issues are happening is on social media. Social media provides a particularly important window into the discourse about racism. The Black Lives Matter movement, for example, has made social media central to its strategy: #BlackLivesMatter was the third-most used social-issue hashtag in the history of Twitter in 2016.6 Many policymakers, journalists, and members of the public have learned or are learning about race, racism, and its impact on communities through the work of the Black Lives Matter and its robust social media strategy.

We wondered, how are childhood trauma researchers, advocates, and others talking about race on Twitter? Are those conversations drawing the connection between trauma and structural racism?

We also wondered whether there were opportunities to bring a trauma lens to existing Twitter conversations about racial justice: Do conversations about Black Lives Matter — which often center on violent and traumatic incidents in communities of color — include discussions of trauma or related topics?

In this report, we present the findings from our exploration of how these conversations intersect on social media and consider the implications for communicating about the intersections of trauma, racism, and racial justice.

What we did

We collected two sets of Tweets posted between July 2014 and December 2016, using the Synthesio social media listening platform.

Childhood trauma: We collected any Tweets that focused on childhood trauma and resilience. We searched these Tweets for any mention of race or racism.

Black Lives Matter: We collected any Tweets that contained Black Lives Matter phrases or hashtags (e.g., #BlackLivesMatter, #BLM). Among these Tweets, we searched for posts that contained keywords relating to trauma and resilience.

We removed Tweets that were irrelevant and those that were privacy-protected by the Twitter user. We also removed Tweets that used the term “trauma” or “traumatized” colloquially, as when Twitter users discussed being “traumatized” by a movie or TV show as a child.

We developed a coding instrument based on our review of existing literature and our previous analyses of ACEs in the news7, 8 and in social media.9 Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process and a statistical test (Krippendorff’s alpha*) to ensure that coders’ agreement was not occurring by chance. For our first level of analysis, we coded only original, unique Tweets, removing Retweets and repeated Tweets.

Then, to explore the structure of these Twitter conversations, we conducted a network analysis, which examines the connections and interactions within a social network. Using Python (a programming language), we mapped the connections between all the Tweets in our sample (including Retweets, mentions, and repeated Tweets**) and then visualized these networks using Gephi, a network analysis and visualization software.

What we found

Race in conversations about childhood trauma

Race was rarely mentioned in Twitter conversations about childhood trauma. Between July 2014 and December 2016, we found 187,062 Tweets that mentioned keywords relating to childhood trauma. Of these, only 2% (n=4,583) mentioned issues of race. To understand how race was discussed when it did appear, we conducted an in-depth analysis of those Tweets.

Twitter users talked about the links between race, racism, and childhood trauma.

Tweets about childhood trauma discussed race in a number of ways. Many of the posts focused on highlighting the scope of the trauma that kids from communities of color experienced. One Twitter user commented, for example, “There are black children in overtly stricken areas who experience the same level of PTSD as children in war torn countries like Iraq.”10

Some Tweets pointed specifically to racism as a cause of trauma, as when Drexel University professor Andre Carrington, linking to an article on epigenetics,3,*** wrote, “#Epigenetics always makes me think of racism as intergenerational trauma.”11 Overall, about one in five Tweets about childhood trauma and race explicitly discussed racism (18%).

Users also described the impact of trauma in communities of color on mental health, physical health, and ability to learn. For example, Mental Health America asserted in one of its Tweets, “racism is a toxic stressor & toxic stress is linked to conditions like depression.”12

The majority of Tweets used the term “trauma,” but resilience was also a prominent term and was mentioned in over a quarter of Tweets (27%). About one in 10 Tweets (9%) discussed some form of intergenerational or historical trauma. PTSD was similarly mentioned in about one in 10 Tweets (9%), while terms relating to ACEs appeared in 8%, and toxic stress in 6%. Most Tweets talked about trauma broadly, rather than discussing specific types of trauma or adverse childhood experiences. When specific types of trauma were mentioned, most were community-level factors, such as exposure to community violence or poverty.

About half of the Tweets (51%) discussed Black children or the experience of Black communities. Native Americans were mentioned in 8% of Tweets, and Latinos in only 5%. When Tweets did mention Native Americans, they were much more likely to discuss intergenerational trauma (27% of Tweets vs. 9% of Tweets overall). One Tweet, for example, linked to a research report and stated, “Trauma & Resilience May Be Woven Into DNA of Native Americans.”13 Like this one, many of the Tweets mentioning Native Americans also focused on resilience (40%). Tweets mentioning Latinos appeared mainly around the 2016 presidential election, often describing the traumatic impact of the election and of Donald Trump’s candidacy on Latino children and communities.

Trauma, race, and the 2016 presidential election.

The 2016 presidential election was a notable Twitter moment — activity across Twitter soared in November 2016.14 The number of Tweets about childhood trauma and race also spiked significantly during this time. In November 2016, about half (49%) of Tweets in our sample discussed the election. Users who were Tweeting about childhood trauma and race discussed how Donald Trump’s candidacy, his racially charged rhetoric, and his divisive campaign platforms caused trauma to children of color. For example, one Tweet linking to a Washington Post article stated: “Southern Poverty Law Center report shows children of color deeply traumatized by 2016 presidential campaign.”15

Tweets rarely mentioned solutions. When they did, they were often vague.

In the Twitter conversation about childhood trauma and race, only a quarter of Tweets discussed any kind of solution. Of these, many were somewhat vague calls for change, such as Tweets that called for “building resilience” in children. This lack of specificity may be at least partially a function of space constraints, since Tweets were limited to 140 characters during the time period we studied.

However, we did find Tweets that called for more concrete solutions, such as school-based actions (27%), access to mental health services (14%), and specific legislation (14%). A local chapter of the Academy of Pediatrics, for example, Tweeted about the need for changes to school policies, calling for counseling and supports for kids of color: “Counsel or Criminalize? Why Students of Color Need Supports, Not Suspension.”16

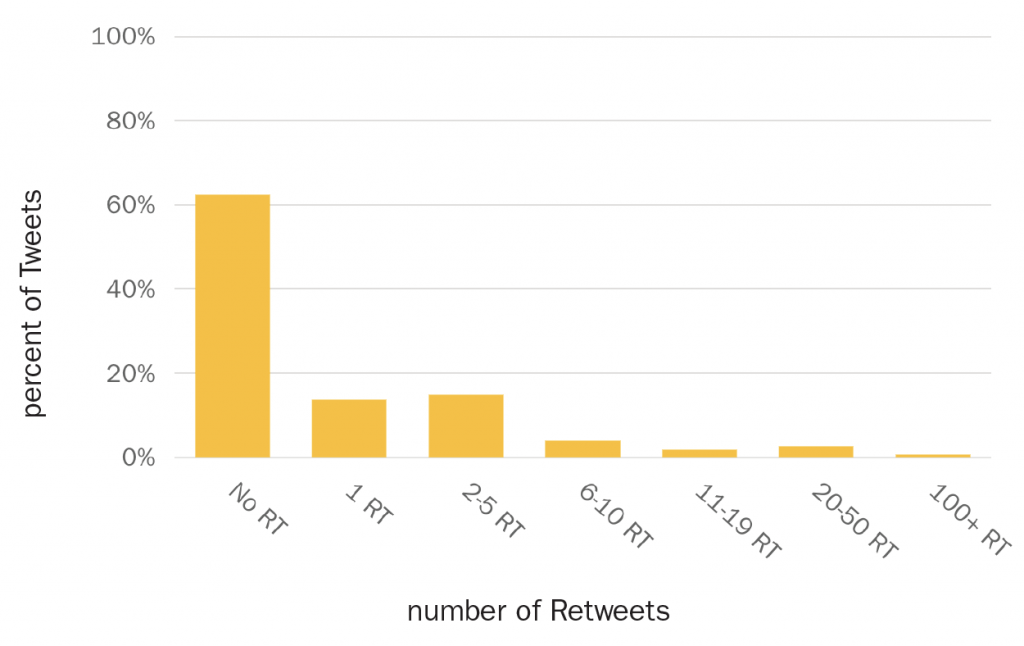

Figure 1: Percent of original Tweets about childhood trauma and race posted July 2014 – December 2016 by the number of Retweets (n=592)

People were rarely Retweeted, but a few Tweets went viral.

We wanted to know not only about what people Tweeted, but how this information spreads and how conversations take place and develop. For this reason, we conducted a network analysis — which examines the connections within a social network — of our sample of conversations about childhood trauma and race. In conversations about childhood trauma and race, there were 592 unique Tweets, and these were Retweeted 2,575 times.

Of the Tweets about childhood trauma and race, a little over a third (38%) were Retweeted or shared. However, when Tweets were shared, they weren’t Retweeted very often: 33% of Tweets were Retweeted 10 times or less, and only 5% of Tweets were Retweeted more than 10 times.

In addition, Twitter conversations about childhood trauma and race tended to be isolated from one another. This pattern is clearly visible in the graphic on the following page: Most networks of Twitter users contain only a few people and are not connected to other networks, suggesting there is not one conversation about childhood trauma and race, but rather many small conversations that are not connected.

However, there were a handful of Tweets (<1%) that were Retweeted more than 100 times. One in particular went “viral” — Marty Lang, a filmmaker and journalist, posted his viral Tweet (Figure 2) on the night of the 2016 election, expressing concern for children of marginalized populations.17 Within hours, his Tweet was Retweeted hundreds of times, reaching far beyond his follower network.

In Figure 2, we illustrate how users who Tweeted about childhood trauma and race were connected (or not connected), and we highlight the most widely shared Tweets about childhood trauma and race.

Figure 2: Network of Twitter users Tweeting and Retweeting about childhood trauma and race from July 2014 through December 2016 (n=3,167)

Trauma in conversations about Black Lives Matter

Conversations about Black Lives Matter on Twitter seldom mentioned trauma. Between July 2014 and December 2016, there were 7,732,281 Tweets mentioning Black Lives Matter. Of these, only 0.004% mentioned trauma or related terms, such as resilience or toxic stress (n=3,169). We conducted an in-depth analysis of those 3,169 Tweets to better understand what discussions of trauma looked like in Tweets about Black Lives Matter.

Tweets discussed trauma caused by police violence.

Unsurprisingly, police violence was one of the most commonly discussed topics in Twitter conversations about Black Lives Matter and trauma (27%). Mirroring patterns in the broader conversation about Black Lives Matter, the conversation about trauma and how it related to the movement was also characterized by a sharp increase in Tweets in July 2016. This notable growth in conversation was prompt-ed by the death of two Black men — Alton Sterling and Philando Castile — at the hands of police in the span of two days, followed by highly publicized protests all over the nation. In fact, Tweets from July 2016 alone comprised over a quarter of the conversation about Black Lives Matter and trauma in our sample (29%).

Much of the conversation that month discussed trauma in the Black community generally, but some Tweets specifically mentioned the trauma experienced by Philando Castile’s 4-year-old daughter, who was in the back seat when he was killed by police during a traffic stop. For example, one Twitter user who shared the video of the shooting commented that “There was a child in the back seat who witnessed all of this happen…imagine having to grow up with that trauma.”18

Overall, most Tweets about Black Lives Matter focused on adults’ experiences of trauma, whether from police violence or other forms of racism. However, as with the above Tweet, there was some conversation about childhood trauma specifically (14% of Tweets). Of these, about half mentioned adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), as when Jenny Welch Buller, an education researcher, included the hashtag #ACEs in a Tweet about a Black Lives Matter call to action: “Just heard call for action from #blacklivesmatter — truth and reconciliation, trauma informed solutions #ACEs #blacklivesmatter.”19

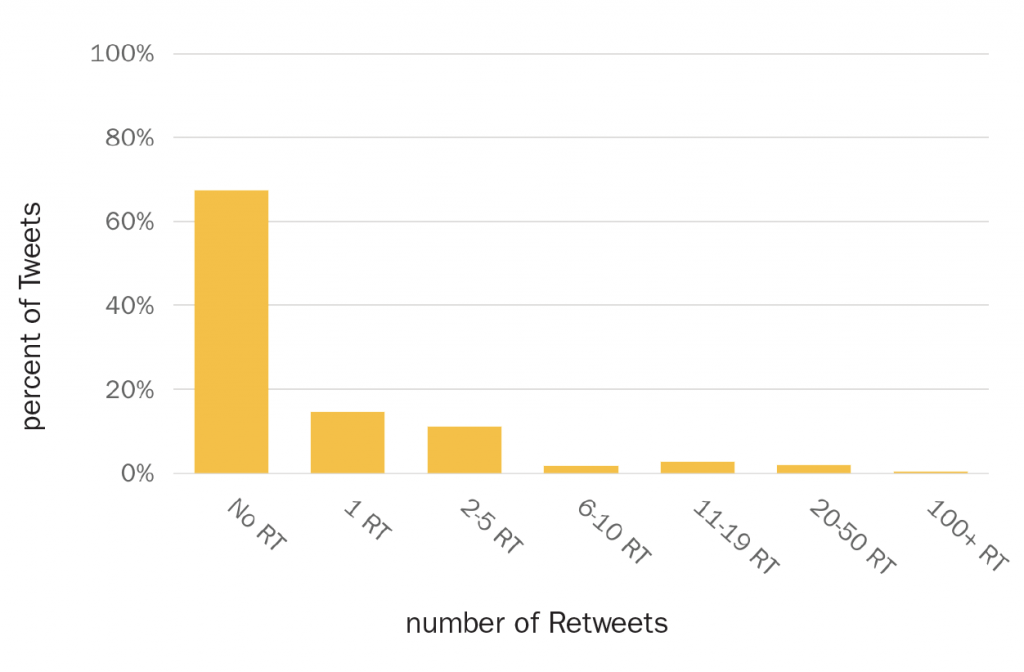

Figure 3: Percent of original Tweets about Black Lives Matter and trauma posted July 2014 – December 2016 by the number of Retweets (n=409)

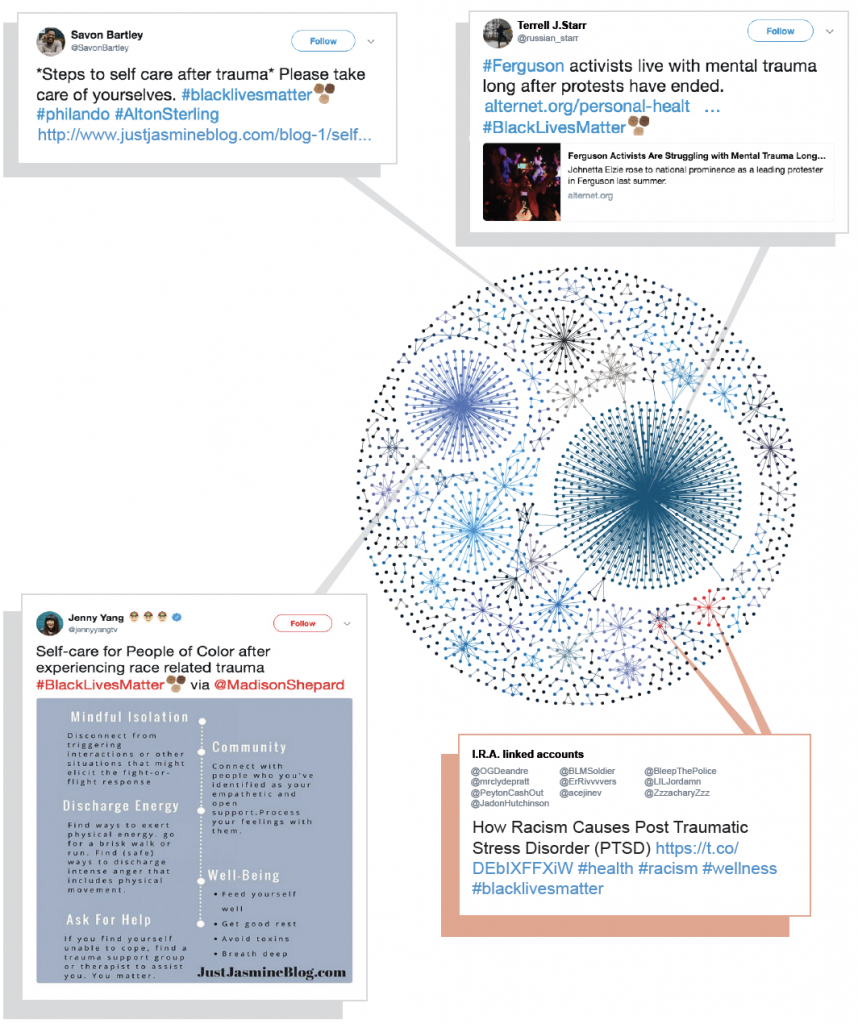

Of solutions mentioned in Tweets about Black Lives Matter and trauma, self-care was the most common.

About a third of Tweets mentioned some kind of solution to address the issues related to Black Lives Matter and trauma. Of these, almost half were about self-care, or tending to one’s own emotional and psychological well-being in response to trauma (46%). For example, A widely Tweeted infographic listed five self-care tips — including disconnecting from triggering interactions, connecting with supportive and empathetic people, and eating and resting well — for people of color after experiencing race-related trauma.20 While self-care is crucial for maintaining one’s physical and mental health in times of stress and trauma, the focus remains on what individuals can do for themselves, rather than on what systems changes are needed to foster healthier communities. Tweets also sometimes discussed access to mental health services (18%), as when a Brooklyn social worker Tweeted, “When I think of structural social change I think of available affordable mental healthcare addressing racial trauma.”21

Conversations about Black Lives Matter and trauma were not well connected.

We also conducted a network analysis of Tweets about Black Lives Matter and trauma, allowing us to examine the structure of these conversations. In our network analysis of Twitter conversations about racism and trauma, there were 409 unique Tweets, and these were Retweeted a total of 1,222 times. A third of Tweets (33%) were Retweeted or shared. However, two-thirds of Tweets were never Retweeted (67%). When Tweets were shared, they weren’t Retweeted very often — 28% of Tweets were Tweeted fewer than 10 times and only 5% of Tweets were Tweeted more than 10 times. Two Tweets were Retweeted more than 100 times.

While there were a few Tweets that had greater engagement, most Twitter networks about Black Lives Matter and trauma tended to be disconnected from one another. This trend is clearly visible in Figure 4: The network visualization shows a pattern of small, isolated conversations, rather than larger, interconnected ones.

Russian-controlled accounts were present in Twitter conversations about Black Lives Matter and trauma.

On November 1, 2017, Congress released a list of 2,752 Twitter accounts that were linked to Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA), an online influence operations company based in Saint Petersburg.22 The IRA was allegedly hired by an ally to Russian President Vladimir Putin to sow discord over social media, or “troll,” to polarize users’ views on social and political issues.23 A portion of these were targeted at inflaming racial tensions and used hashtags such as #BlackLivesMatter and #BLM. A handful of these Tweets from IRA-linked accounts also discussed issues of trauma and were therefore pulled into our sample.

We found Tweets from 10 users identified in the IRA list in our sample, with handles ranging from “@ZzzacharyZzz” to “@BLMSoldier.” These accounts all posted the same Tweet: “How Racism Causes Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) https://t.co/DEbIXFFXiW #health #racism #wellness #blacklivesmatter,” on March 31, 2016. The Tweet links to a now-defunct website, “improvingyourwellness.com,” and appears to mimic language used in Tweets from the month before about the work of Dr. Jonathan Shepherd, a Maryland psychiatrist and researcher.

We also found a handful of other Twitter users in our sample who were not on the IRA list but interacted with the IRA-linked accounts and, based on their profiles and user behavior, also seem likely to not be legitimate accounts. We highlight these accounts in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Network of Twitter users Tweeting and Retweeting about Black Lives Matter and trauma from July 2014 through December 2016 (n=1,631)

Conclusion

In a time of racially charged and divisive political rhetoric, it is vital to examine the intersections between racism and long-term trauma to improve how we communicate effectively about both. To explore if and how these intersections were being discussed on social media, we analyzed the content and networks of two categories of Tweets: Tweets about childhood trauma and race, and Tweets about Black Lives Matter and trauma.

We found that Twitter conversations about childhood trauma and race rarely intersected: Few Tweets about childhood trauma mentioned race, and very few Tweets about Black Lives Matter mentioned themes relating to trauma. Additionally, few Twitter conversations about race and trauma included solutions and strategies to address these issues.

But we know it is possible to link these issues, even in something as short as a Tweet. When Twitter users did talk about race and childhood trauma, they often made powerful connections between the experiences of kids of color and manifestations of structural racism, such as harmful rhetoric in the 2016 presidential election and police violence. In addition, Tweets that discussed both Black Lives Matter and trauma contained nuanced conversations about the scope and impact of trauma as a result of issues like police violence. However, most conversations happened among just a few people, and only a handful of Tweets had a wide reach.

Our findings suggest that there are opportunities to address the gaps between childhood trauma and structural racism in social media conversations. Taken as a baseline, our findings indicate that researchers and advocates working at the intersection of childhood trauma and structural racism could have a unique opportunity to shape the social media conversation by more frequently making those intersections explicit and by elevating authentic voices and conversations that are already taking place. To that end, we offer the following recommendations:

Build out your network and elevate conversations that make connections between trauma and structural racism.

Twitter is all about conversations. We found that Tweets that make connections between trauma and racism are nuanced and authentic, but they are rarely Retweeted nor responded to. Before posting, take the time to “listen” to and engage with Twitter conversations about trauma and racism that are already happening, particularly within communities of color that are disproportionately affected by trauma. Identify the authentic voices who are talking about the trauma of structural racism so you can see conversations as they happen. Follow Twitter accounts that focus on racial justice issues and elevate these voices by replying to, commenting on, Retweeting, and liking posts that make important points about the intersection of trauma and race. Mention fellow advocates in your comments and Retweets to loop them into conversations about trauma and racism.

Draw connections to trauma in conversations about Black Lives Matter.

Tweets about Black Lives Matter, one of the defining social justice movements of this decade, rarely discuss trauma explicitly. This presents a strategic opportunity for advocates to make trauma a part of the conversation as it relates to violence against people of color. To elevate this intersection, follow hashtags and accounts that advocate for Black Lives Matter, and then engage with — Retweet or reply to — these Tweets using a trauma lens. For example, Retweet or comment on Tweets about police violence, racial profiling, and inequality by providing a trauma-informed perspective. In your responses, raise questions such as, “How does this issue affect people of color and their mental/physical health?” or “How can we support and empower people of color to address trauma caused by these issues?”

Talk about childhood trauma with a racial equity lens.

Tweets about childhood trauma that made connections to issues of structural racism were rare, and childhood trauma advocates should work to expand this conversation. When discussing childhood trauma on Twitter, be sure to highlight how trauma affects children of color disproportionately. Twitter conversations are also a good opportunity to describe the links between trauma and structural racism. We saw examples of these connections being made in Tweets discussing intergenerational trauma or toxic stress caused by discrimination. One way to spark conversations about these links is to host Tweet chats about topics related to trauma and racism. Bringing these intersections into focus will help to create a more complete and nuanced picture of childhood trauma in social media conversations.

For more ideas about how to use Twitter to shape the conversation about trauma and racism, please see https://www.bmsg.org/blog/5-ways-advocates-can-use-twitter-elevate-link-between-racism-and-childhood-trauma.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Laura Nixon, MPH, Sarah Han, BA, Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH, and Lori Dorfman, DrPH. Thanks to our colleagues at Berkeley Media Studies Group for their research and writing support, especially Heather Gehlert and Lauryn Claassen. Thank you to Daphne Marvel, BA, and Vanessa Palzes, MPH, for research assistance, and to Alex Estes, PhD, and Vanessa Palzes, MPH, for their assistance with the data analysis.

This work was supported by The California Endowment. Specifically, we thank Mary Lou Fulton for her insights and support. Thanks also to everyone who participated in the Racing ACEs meeting, held in Richmond, California, in September 2016.

Twitter, Tweet, Retweet, and the Twitter logo are trademarks of Twitter, Inc. or its affiliates.

The sources of the graphics in this report are as follows: “Network” icon by Barracuda pg. 6, “Bot” icon by Jugalbandi pg. 13, “Listen” icon by Rémy Médard pg. 15 from the Noun Project.

© 2018 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

* We achieved an acceptable reliability measure of >.8 for each variable. See: Krippendorff K.(2009). The Content Analysis Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

** We considered a network connection to be when one user mentioned another user in their Tweet or when a user Tweeted another user’s content. We identified original Tweets and Retweets using timestamp data, user mentions, and string similarity as measured by Levenshtein distance. We use the term “Retweet” to include all Tweets that repeat the content of the original Tweet.

*** Epigenetics is the study of how social and other environments, including childhood trauma, turn our genes on and off. This can lead to long-term physical and mental changes, which can be transferred from generation to generation.

1. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/.

2. Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. Toxic stress. Retrieved from: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/.

3. ACEs Too High. ACEs 101. Retrieved from: http://acestoohigh.com/aces-101/.

4. Stevens J. (2015). Adding layers to the ACEs pyramid — What do you think? Retrieved from: http://www.acesconnection.com/blog/adding-layers-to-the-aces-pyramid-what-do-you-think.

5. RYSE Center, Berkeley Media Studies Group. (2016, October 19). Reflected. Rejected. Altered: Racing ACEs revisited. Retrieved from: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/rejected-reflected-altered-racing-aces-revisited.

6. Anderson M., & Hitlin P. (2016, August 15). Social media conversations about race. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/08/15/the-hashtag-blacklivesmatter-emerges-social-activism-on-twitter/.

7. Dorfman L., Mejia P., Cheyne A., & Gonzalez P. (2011, May 1). Issue 19: Case by case: News coverage of child sexual abuse. Retrieved from Berkeley Media Studies Group website: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-19-case-by-case-news-coverage-of-child-sexual-abuse.

8. Nixon L., Rodriguez A., Han S., Mejia P., & Dorfman L. (2017). Issue 24: Adverse childhood experiences in the news: Successes and opportunities in coverage of childhood trauma. Retrieved from Berkeley Media Studies Group website: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-24-adverse-childhood-experiences-trauma-news-coverage-successes-opportunities.

9. Nixon L., Somji A., Mejia P., Dorfman L., & Quintero F. (2015). Talking about trauma: Findings and opportunities from an analysis of news coverage. Retrieved from Berkeley Media Studies Group website: https://www.bmsg.org/sites/default/files/bmsg_talking_about_trauma_news_analysis2015.pdf.

10. Wat_The_Mell. (2016, October 26). There are black children in overtly stricken areas who experience the same level of PTSD as children in war torn countries like Iraq [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/Wat_The_Mell/status/791445030791553024.

11. prof_carrington. (2014, October 18). #Epigenetics always makes me think of racism as intergenerational trauma [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/prof_carrington/status/523495550629707776.

12. MentalHealthAm. (2015, July 7). Racism is a toxic stressor, & toxic stress is linked to conditions like #depression – @APA offers some coping tools: [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/MentalHealthAm/status/618492188435984385.

13. adamsken. (2016, October 11). Trauma & Resilience May Be Woven Into DNA of Native Americans http://ictmn.com/4wvX via @IndianCountry #Epigenetics #indigenous #DAPL [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/adamsken/status/785939372591808512.

14. Isaac M., & Ember S. (2016, November 8, 2016). For election day Influence, twitter ruled social media. The New York Times.

15. ndngenuity. (2016, April 14). Southern Poverty Law Center report shows children of color deeply traumatized by 2016 presidential campaign – https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2016/04/13/the-trump-effect-report-says-children-of-color-are-deeply-traumatized-by-2016-campaign/ [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/ndngenuity/ status/720579391978389506.

16. WIAAP. (2016, September 23). Counsel or Criminalize? Why Students of Color Need Supports, Not Suspensions https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education/report/2016/09/22/144636/counsel-or-criminalize … via @AmProg #poverty #trauma #ACEs [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/WIAAP/status/779280106992836608.

17. marty_lang. (2016, November 8). What will immigrant children feel like at school tomorrow? LGBTQ kids? Black kids? Girls? A national trauma is about to begin #ElectionNight [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/marty_lang/status/796224071499333632.

18. JohanCasal. (2016, July 6). But there was a child in the back seat who witnessed all of this happen – imagine having to grow up with that trauma [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/JohanCasal/status/750924230317879296.

19. JenWelchBuller. (2016, July 13). Just heard call for action from #blacklivesmatter truth and reconciliation, trauma informed solutions #ACES #blacklivesmatter [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/JenWelchBuller/status/753371506818842625.

20. Banks J. (2016) Self care for people of color after psychological trauma. justjasmineblog.com. Retrieved from: http://www.justjasmineblog.com/blog-1/self-care-for-people-of-color-after-emotional-and-psychological-trauma.

21. rariella. (2016, February 15). When I think of structural social change, I think of available affordable mental healthcare addressing racial trauma [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/rariella/status/699350349371482112.

22. Frommer D. (2017, November 2). Twitter’s list of 2,752 Russian trolls. Recode.

23. Lukito J., Wells C., Zhang Y., Doroshenko L., Kim S.J., Su M.H. (2018 February). The Twitter exploit: How Russian propaganda infiltrated U.S. news. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison.